The boy-girl standard for New Dutch Writing

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (pronoun: they/them) wins the International Booker prize, after some sensitivity nonsense - "gevoeligheidsflauwekul" - in the English translation.

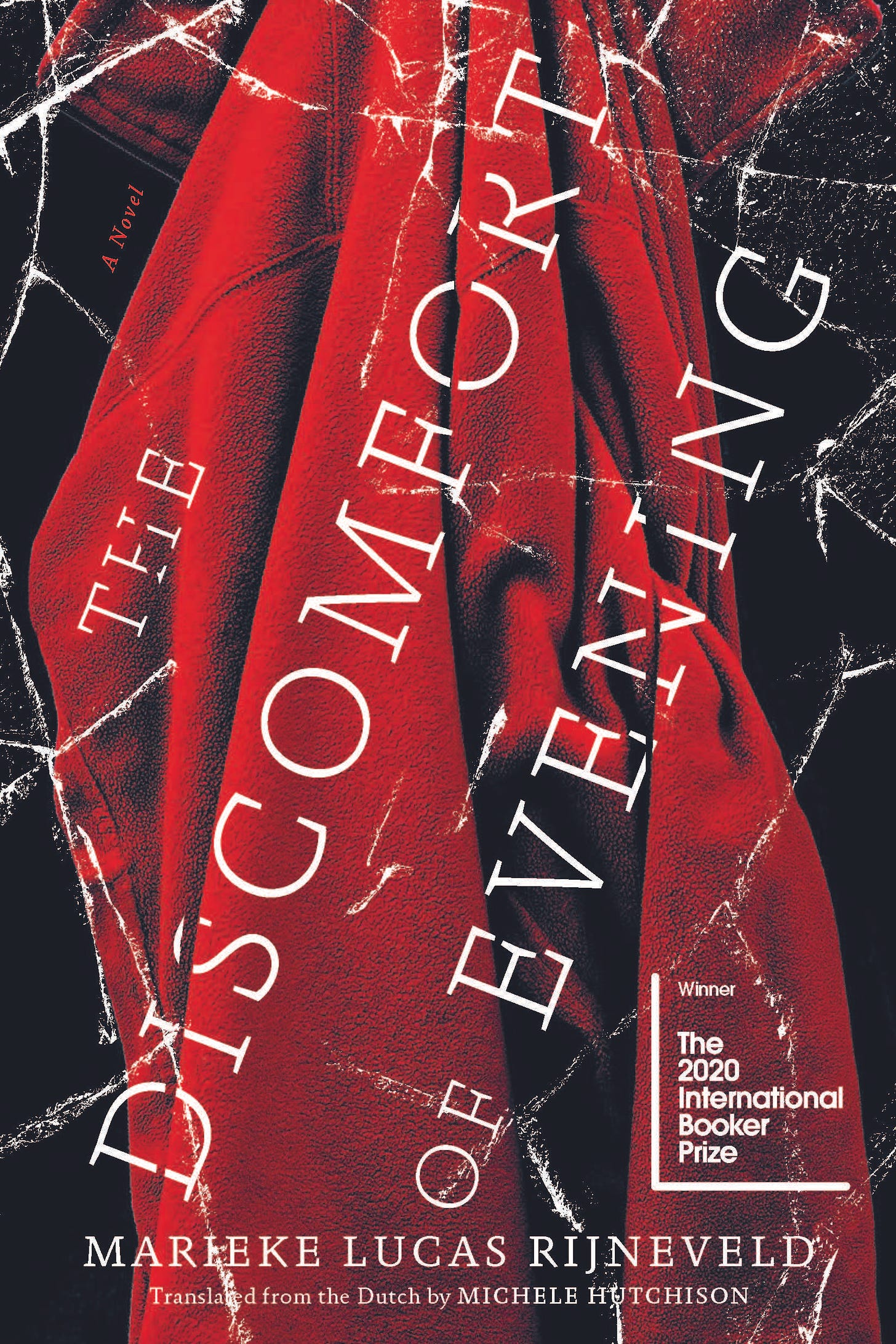

Praised for the vicious comedy - venijnige komedie - and pure poetry of their writing, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld is the first Dutch author to win the International Booker prize for their first novel, The Discomfort of Evening - De Avond is Ongemak (2018).

Not another old man of letters with furrowed brow - met een doorgroefd gelaat, wrote Wilma de Rek in the Volkskrant. Rijneveld, who identifies as non-binary (hence the personal pronoun: they) is a 29 year-old skinny boy-girl - een tenger jongensmeisje. And not just a writer, but a farmer. Rijneveld grew up in an oppressive religious family on a dairy farm in Brabant, and still works today on a dairy farm outside Utrecht.

Her novel, a portrait of unarticulated family grief in the rural hinterland, opens with 10 year-old Jas venting her anger at not being allowed to go ice-skating with her older brother Mathies. Jas prays to God to spare her pet rabbit from the Christmas dinner table and to take her brother instead. Then Mathies falls through the ice.

This grim, grievous story drew praise from English critics, although in translation some notable passages were excised. Jas tries to ward off the pain and sorrow with strange, sexual, sometimes morbid experiments on animals -- de pijn en het verdriet te bezweren met vreemde, seksuele, soms morbide experimenten op dieren, wrote Paola van de Velde in the Telegraaf.

An “uncomfortable” joke, familiar to all Dutch children, was dropped from the English translation

Rijneveld, who lost her own brother at a young age, is an admirer of writer Jan Wolkers (1925-2007), a towering figure in the Dutch literary canon. Shared themes include the dead brother, and a fascination for animals, faith and sexuality. While writing, Rijneveld posted a note above her desk: Onverbiddelijk zijn. Be relentless.

Rijneveld reveres Wolker above all for his beautiful language - “vooral zijn prachtige taal”, but they are scrupulous in differentiating their own voice. Where Wolkers recoiled at the Reformed Church to reckon with the distress caused by a cruel god - rekende meer af met de benawdheid, Rijneveld is less concerned with resistance. They doesn’t wield the pen as a weapon - “wil niet de pen als een wapen gebruiken”.

A cow with seven udders

Winning the International Booker made them as proud as a cow with seven udders, “een koe met zeven uiers”. To Wilma de Rek in the Volkskrant, this surprising turn of phrase was a fine variation - een fijne variant - on a better-known alpha male expression - op de alfamannetjesuitdrukking: to be as proud as a monkey with seven dicks - zo trots als een aap met zeven lullen.

The £50,000 prize, to be shared equally between author and translator, also recognises English translation by Michele Hutchinson, who has already collected the 2020 Vondel Translation Prize for another Dutch novel, Stage IV by Sander Kollaard. Translating Rijneveld is daunting work, as Hans Bouman explained in his review. The challenge is to bring a hinterland of primeval Dutch details -- een wereld vol oer-Hollandse details -- to life for readers in English.

The world of the novel is as exotic and strange as reading a fat Russian - als ik een dikke Rus lees, said Bouman. For Hutchinson, the task was to determine just how many extra words are necessary in English without disturbing the rhythm of the Dutch novel. Its pages are populated with Frisian runners (antique ice skates), gravy pits (potatoes with holes, meatballs) and other obscurities. A huzarensalade becomes, literally, a Russian salad. Sinterklassjournaal is simply a pre-Christmas show.

Other elements of the Dutch original didn’t make the cut. The Black Petes - Pieten - on the roof of the family home were excised (they require “too much explanation,” according to English publisher Graywolf Press). An “uncomfortable” joke, said to be familiar to all Dutch children at the time, was also deleted from the English version:

“Waarom pleegde Hitler zelfmoord?” Why did Hitler commit suicide?

“Omdat hij de gasrekening niet kon betalen” Because he couldn’t pay the gas bill.

To date, only British publishers have shown such qualms. Rijneveld is curious to see if it re-appears in a new print run: they really struggled with it - “Ze hadden er echt moeite mee”. But translation is also transaction: by sacrificing the ‘joke’, other sentences and metaphors survived intact.

Even so, De Rek was horrified at the omission. Urging the publisher to restore the redacted line in the next edition, she saw no virtue in deferring to this sensitivity nonsense - niet meedoet aan gevoeligheidsflauwekul. Hutchinson herself was sanguine, acknowledging that in British culture the joke would become a distraction. For the Anglo-Dutch translator, who describes herself as living between two cultures, the joke “can’t be done”.

On the aspects of fragility

Winning prizes makes Rijneveld a reluctant standard-bearer for what’s becoming known as New Dutch Writing. Their poetry collection, Fantoommerrie, also picked up this year’s Ida Gerhardt Poetry Award. But the public acclaim, while craved, complicates the lonely graft of a novelist and poet.

Rijneveld acknowledges the desire to be seen, even as they finds themselves ill-equipped to deal with the attention. Interviewed by Toef Jaeger for a profile in NRC, they observed that the acclaim doesn’t change the fragility which drives and enables their writing - “de wankelheid zorgt er ook voor dat ik kan schrijven”. They had felt incapable of dealing with the spotlight.

As a non-binary person, who recalls once explaining to their parents that she is a boy, the exposure conferred some legitimacy. They have been able to talk about gender: to show they are still searching - “Zo kon ik laten zien dat ik nog zoekende ben” - and experienced relief (that was “nice”) at being accepted as non-binary. Now, they feel more steadfast in the knowledge that they don’t have to choose.

Coronavirus has brought some relief too. In place of the stress associated with readings and stage appearances, Rijneveld’s newfound public persona as a writer has fallen away. They are left to their former solitary life of writing, walking, tending to the cows.

And what of the New Dutch Writing, promoted enthusiastically by the Dutch Foundation for Literature, with a newfound audience especially in Britain?

The new genre spans at least two distinct categories, explained the Volkskrant. In non-fiction, British readers like the documentary formats of long, well-written journalism, not least because less space is available for that in British newspapers. In fiction, the audience taste is more particular - houden Britten van de donkere sfeer en van het platteland. Brits love the dark atmosphere of the countryside.