The price for getting clean

Oil and gas firms want subsidies for carbon capture and storage: why?

Taking carbon out of the air and into the ground is a crucial step to prevent climate breakdown. In the Netherlands, four new large-scale carbon capture and storage facilities are in development - including Porthos, an offshore project outside Rotterdam.

The United Nations’ Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change says that CCS plants are vital to do the heavy-lifting (more accurately: sinking) to reduce carbon emissions. Worldwide, fewer than 25 big projects are currently active and we're far behind all the prospective IPCC scenarios. So we need more CCS. Fast.

That won't happen without public subsidies, but Porthos, an empty North Sea gas field, is controversial.

Financieele Dagblad reported that four multinationals - Shell, ExxonMobil, Air Liquide and Air Products - will apply for state aid to create a ‘carbon sink’ to capture carbon dioxide sequestered from the atmosphere.

Offshore CCS at this scale represents a new threshold for the technology. FD journalist Carel Gro rated the chances of success as pretty high: a breakthrough experiment, he said, because it doesn’t yet exist - omdat het nog niet bestaat.

Carbon capture, storage and other applications are known as the “greening” of Dutch energy facilities, or SDE for short - vergroening van de Nederlandse energievoorzieningen. Porthos would be the first of a kind, but does its consortium deserve public subsidies?

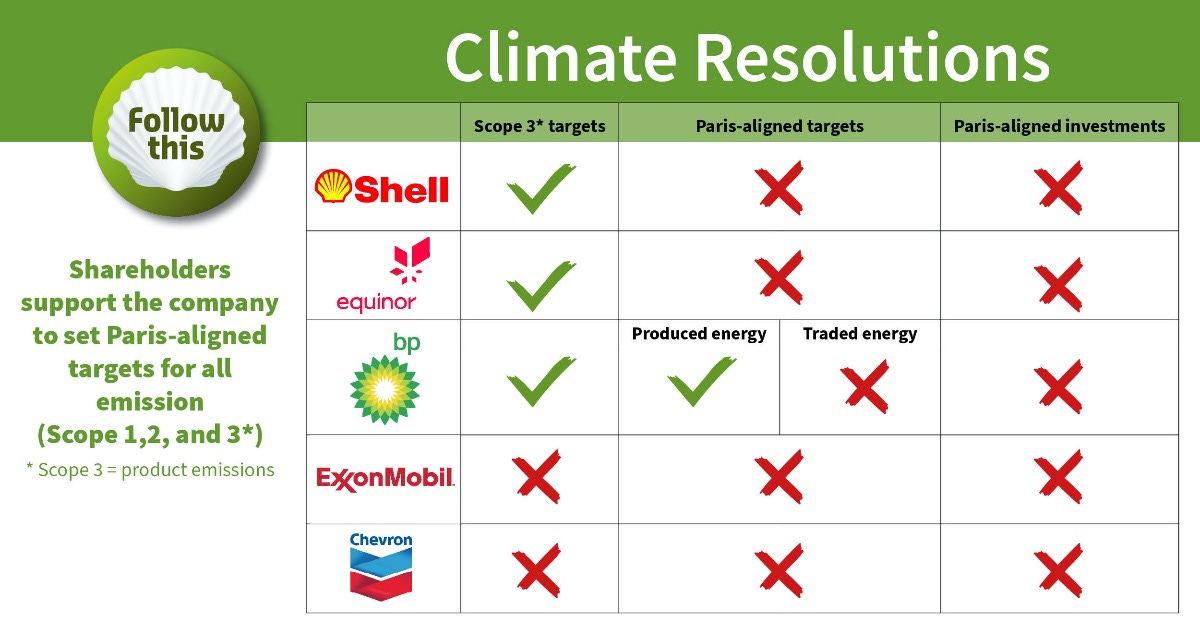

No, said Mark van Baal, founder of Follow This, a Dutch shareholders’ movement which files climate resolutions at the annual meetings of oil and gas companies whose products generate greenhouse gas emissions.

Getting clean is junkie terminology, reflecting our long addiction to energy from fossil fuels and dividends from petrodollars

Van Baal wants them to first do everything possible - alles aan doen, to replace fossil energy with sustainable energy - om fossile energie te vervangen door duurzame energie. Until then, Big Oil should be ineligible for subsidies - zouden ze niet in aanmerking mogen komen, he argued.

His stance drew a swift response - for and against. “We have to clean up, and fossil fuels should take the lead on this,” wrote Margriet Kuijper, a consultant, on LinkedIn. “CCS is like offsetting - the last option after you have done everything else possible to avoid, minimise and reduce,” posted Hans Friederich, who works in nature-based development solutions.

Clean up or get clean?

When the money's gone, it's gone. FD reported that €5 billion in public subsidies is expected for SDE in the Netherlands, of which €1.5 billion will be earmarked for CCS. At Porthos, the Shell-Exxon consortium could ask for pretty much all of that.

Elsewhere, most of Europe's new CCS plants capture carbon dioxide from industry. Other big projects underway include six in the UK - notably Acorn, Teesside and Zero Carbon Humber - with one more planned in each of Ireland and Denmark. Two big Norwegian plants are operating at Snøhvit and Sleipner.

Typically, CCS is deployed in energy-intensive sectors such as cement, power generation and heavy manufacturing - all big emitters, with no alternative means currently available to reduce emissions. In the scramble for subsidies, no doubt it helps that their products are essential to the infrastructure for a new low carbon economy.

We have no plans to develop a next generation internal combustion engine - Markus Schaeffer, Daimler

A different case can be made for subsidising CCS by multinational oil and gas producers, a.k.a. “Big Oil”. They bring unique know-how in managing capital-intensive energy infrastructure, on- and offshore. That could be combined with some of the pioneering waste-to-energy converters, or in hydrogen production - fast-growing sectors that would accelerate the transition from fossil fuels.

Fair enough, perhaps. But talk is cheap. The better, more material question may be: what would it take to persuade old energy incumbents, the big oil and gas producers, to abandon fossil energy altogether? To leave the carbon in the ground?

Instead of asking what these companies can do to clean up their emissions, why not ask them to get clean? To harness their financial muscle, project management and market-making power rapidly to scale a clean system of renewables.

If this sounds idealistic, it’s the kind of language that oil company CEOs are talking. None expect to secure their future in the fossil fuels which have made them what they are today. After decades of lobbying against action to curb emissions (in some cases, funding climate change denial by mercenary think tanks and public relations firms), many oil producers now talk with enthusiasm about prospects for post-carbon energy.

Of course, the whole notion of Big Oil ‘getting clean’ is junkie terminology, but that’s appropriate too: a reflection of the modern world's deep dependence on energy from hydrocarbons and dividends from petrodollars.

How to wean us all off this addiction - producers and consumers alike - is humanity's most urgent challenge, an existential dilemma. Forecasts diverge. Carmakers and oil companies, for example, seem to inhabit different worlds. But the direction of travel is not in doubt: “We have no plans to develop a next-generation internal combustion engine,” Markus Schaeffer, Daimler’s development chief, told Auto Motor und Sport magazine in 2019.

In the past year, publicly traded oil companies including BP, Equinor, Shell and Total have announced new (non-binding) climate “ambitions” to curb emissions by 2050. Talking up their green credentials makes them sound, inevitably, like repentant sinners.

Are they credible? “If oil and gas companies would NOT have put forward plans for SDE++ that would really have been far more shameful then asking for subsidies for these first-of-a-kind projects,” posted Margriet Kuijper.

An example from the Netherlands

Calls for businesses to report on climate risks are becoming stronger - klinkt de roep om bedrijven over klimaatrisico’s te laten rapporteren steeds sterker, reported NRC. In November 2020, a group of 38 European investors - including Dutch funds Robeco, Aegon and MN - wrote to 36 investee companies to urge more disclosure on climate risks.

Recipients of their letters included BP, Shell and other oil producers, carmakers Renault and VW, airline Lufthansa, steelmaker ThyssenKrupp and natural resources trader Glencore. For all these companies, stricter measures to curb emissions threaten profits, while failure to stop climate change is causing irreparable damage to the global economy.

The Netherlands, where Follow This cut its teeth in negotiations with Shell, is at the forefront of this climate activism by shareholders. Thanks in part to the oil company's unique history: founded in 1907, with a dual listing on stock exchanges in London and Amsterdam, Royal Dutch Shell is a conspicuous hybrid: part-national champion, but - in many Dutch minds - part-national liability too.

Shell is by a wide financial margin the jewel in the crown of Dutch industrial heritage: a prospective challenger, before the pandemic, to Exxon Mobile’s world title of “biggest oil company” by market value. But Shell's chequered past includes doing business in apartheid South Africa, environmental destruction in the Niger Delta, and numerous local controversies closer to home.

The combination of a high public profile with deep-rooted scepticism made Shell a natural target for activists. Since 2016, Follow This has filed a shareholder resolution at its annual meetings to seek binding emissions targets aligned to the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement. Within two years, by 2018, nine of the 10 biggest Dutch investors either supported or abstained from voting on the Follow This proposal.

These institutions, while huge in terms of assets, comprise only a small proportion of Shell’s global investor base. To date, Follow This resolutions have been routinely defeated. But such is the public scrutiny that for a Dutch institution to side unquestioningly with Shell’s board on this issue would incur a reputational risk to their retail business in asset management, banking and pensions. “Big Oil can make or break the Paris Climate Agreement,” van Baal often tells shareholders.

Unlike other environmental movements such as Greenpeace or Extinction Rebellion, Follow This describes its resolutions as designed to “support” oil companies. Only with a mandate from shareholders, it claims, can Big Oil executives lead the transition to renewables. A significant, growing minority of shareholders (up to 27% in the 2020 AGM season) have voted in favour of these resolutions.

Net Zero

The Paris Climate Agreeement, adopted in 2016, commits almost all the world’s governments - soon to include, again, the United States under President-elect Joe Biden - to limit global heating to well below two degrees above pre-industrial levels, with a target of 1.5 degrees. Taking its cue from the IPCC scenarios, the European Union has set a goal of reducing carbon emissions to “Net Zero” by 2050.

Whatever future awaits Big Oil beyond 2050, it won’t be in fossil fuels. Net Zero means a new way of life, no longer warmed by gas central heating, nor powered by internal combustion engines. The term has penetrated deep into political and economic scenarios in a short period of time - in korte tijd diep doorgedrongen in politieke en economische scenario's, reported NRC.

Hence the multi-billion dollar question: what, if anything, should we do to help Big Oil to get clean?

Conventional wisdom is that incumbents in any industry are eclipsed over time by new entrants with better technology (what economists call Product Lifecycle Theory). This is happening now to Big Oil, according to investment bank Goldman Sachs. It forecasts that new investment in clean energy will surpass upstream oil and gas for the first time in 2021, eclipsing fossil fuels, and building to $16 trillion by 2030.

Goldman's analysis is worth a closer look, even with the financial jargon: “Hurdle rates – a measure of risk akin to weighted average cost of capital (WACC) – for today’s fossil fuel projects are calculated around 10-20% whereas renewables are in a much safer 3-5% range,” explains Mark Campagnale, founder of Carbon Tracker Initiative, a London-based organisation which does what it says on the label. “Money likes to go where risk is lowest,” he adds.

A timed test

Little wonder then that oil and gas incumbents, energy suppliers to the world, are eyeing a bigger stake in the new renewables sector. In a nutshell, they plan to buy into renewables with the profits from fossil fuels.

In the course of the coronavirus pandemic, BP and Shell have written off billions of dollars in oil assets by closing down rigs and mothballing exploration. To help balance the books, both companies plan to ramp up their (lower emissions) natural gas production and expand their energy trading business.

Although keen to talk about their plans to invest in renewables, BP, Shell and Total all anticipate “transition” periods of rising emissions in the short term, at least until 2030. Compensating for lost revenue from oil production with more traded energy won’t help the Paris goals, nor week us off our old addiction.

From most current strategies, it appears likely that Big Oil is preparing to cede its least viable interests in upstream production, the work of extracting oil and gas, to more competitive - often state-controlled - rivals in China, Russia and Saudi Arabia. These firms are still harder to influence.

At the same time, while Big Oil may be learning the new global idiom of climate anxiety - taking its cue from Shell, the first fossil fuel producer to acknowledge publicly the reality of climate change - executives prefer to frame their plans in terms of non-committal “climate ambitions”, based on often elaborate calculations of unknowable scenarios. The complexity of this debate may actually slow the growth of a low-carbon economy.

Resistance from oil company boards to proposals for binding emissions targets - aligned to Paris - is a very public index of their intentions. Making subsidies available for these companies to implement CCS may be necessary to deploy a critical technology, but at this juncture it will also, inevitably, prolong the life of a business model still yoked to fossil fuels.

In the fullness of time, a compromise might be found. The ‘normal’ product lifecycle will take its course, helped by the surge in clean energy investment as new entrants build the infrastructure for a post-carbon, fossil fuel-free economy. But fullness of time is a luxury that we don’t have. As the American activist and writer Bill McKibben puts it, climate change is “a timed test not a generational shift”.