The coronavirus has fuelled extremist opinion in the Netherlands, making social unrest more visible both online and in the streets. Announcing a regular update to the terrorist threat assessement, Dreigingsbeeld Terrorisme Nederland (DTN), national coordinator for counter-terrorism and security (NCTV) Pieter-Jaap Aalbersberg cited social media posts by the radicalised far-right as a factor in the ‘significant’ level of risk.

The ‘significant’ rating is the third of five on the NCTV’s scale (one indicates no risk from terrorism, five signals that an attack is imminent). Polarised debate with sharp edges - met scherpe randen - since the outbreak of Covid-19 is listed on the NCTV website before other risks, including Salafist Jihad and the conflict in Syria. Threats of violence - Rechts-extremistische geweldsdreiging - are conceivable - voorstelbaar, said Aalbersberg.

On the day the DTN was published, public broadcaster NoS removed the logos from its outside broadcast units. Marcel Gelauff, NoS news editor-in-chief, lamented the decision which followed “months” of intimidation of its reporters and television crews. The move is a measure of declining tolerance in the Netherlands, he said: of how deep we’ve sunk - “Zo diep zijn we gezonken”.

The change in public attitudes to the mainstream media over a short period of time was amazing - “verbijsterende”. Besides verbal abuse, harassment included rubbish thrown at NoS staff, dangerous overtaking of its vehicles, and incidents of banging on the sides or urinating on NoS vans. The broadcaster is worried not just by what had happened, said Gelauff, but also by what could yet happen - “angst dat je wat overkomt of wordt aangedaan”.

The DTN makes a distinction between an upper layer of activists and extreme undercurrents. The first category - een activistische bovenlaag - is described as relatively broad and blended - die relatief breed en gemêleerd. The radical elements - radicale onderstroom - are identified by their extreme behaviours. The report is the 53rd update of the DTN, a trend analysis of radicalisation, extremism and threats from national or international terrorism intended to guide policymakers and government operations.

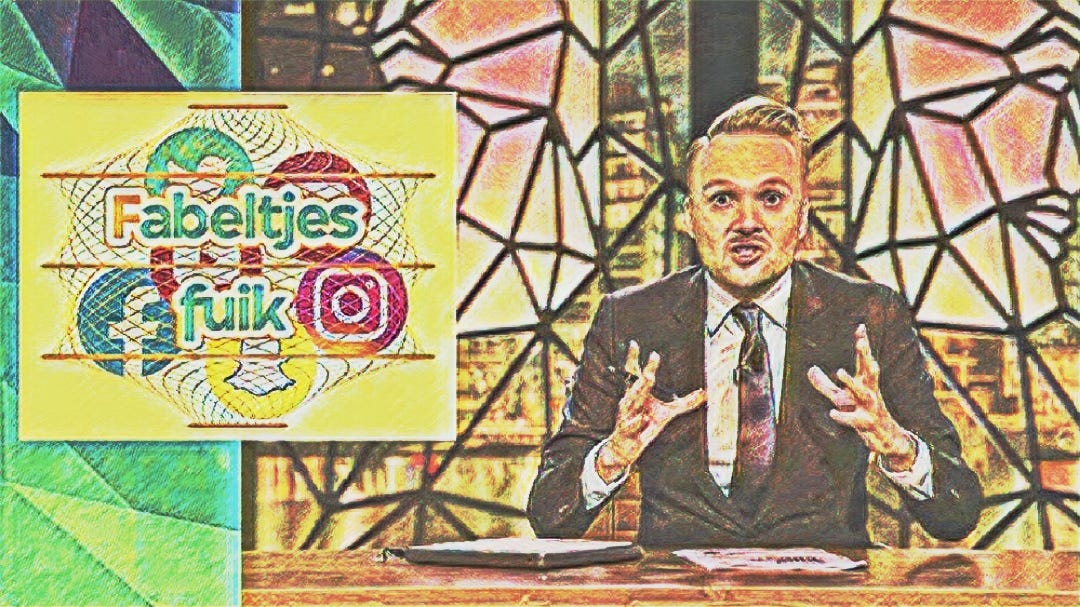

Lubach deploys his 20th century terrestrial television format as a sledgehammer to crack a nut, namely his slow-moving target Lange Frans

The numbers in the report are vague. Extremist factions may consist of perhaps a few dozen people - enkele tientallen. These include anti-lockdown protesters, farmers, football hooligans. Spanning individuals and groups, this radicalised fringe tends not to join political organisations. They find common cause in rejection - vindt elkaar in het afwijzen - of the government or its policies, wrote Aalbersberg. Grievances are amplified via social media, where the threshold - de drempel - for extremist behaviour has lowered.

Last month, a list of the home addresses of cabinet ministers and two journalists was shared online via Telegram, a heavily encrypted messaging app. The linked account belonged to Wes Mylana, one of a small group of protesters who in August harassed Pieter Omtzigt, parliamentary leader of the CDA Christian democratic party, during an anti-lockdown demonstration in The Hague.

The terror of Frans Lange

On his long-running Sunday television show, Arjen Lubach, host of VPRO’s Zondag met Lubach, strode through the quicksands of the radicalised social media maelstrom with his signature brio. After a whistle-stop tour of hard-to-credit vlogs and podcasts, Lubach embarks on a systemic critique of the algorithms which deliver this content to our screens. Setting up a new browser on his laptop, he types ‘coronavirus’ into the search box and dives into the abyss.

Conspiracy Rappers is an apt term, implying a lyricist’s gift for macho tales of exponential invention and offensiveness

It takes just three clicks to surf from online grumbling about the Dutch lockdown, to denials of the 9/11 attacks on New York’s Twin Towers, to the shock jock’s lexicon of Deep staat, Vieze pedofilen (Dirty pedophiles). Landverrader! (Traitor!) and Kinderverkrachter! (Child rapist).

It’s the kind of talk to which Tipper Gore, wife of former deputy US president Al, might argue for attaching ‘Parental Advisory’ stickers, as she did successfully for explicit violent or sexual content on rap CDs in the 1990s.

Lubach found news footage of an anti-lockdown protester on Museumplein in Amsterdam, who believed that abusing children is a part of the lifestyle of the elite. Another, a woman with smart glasses and a neat blonde bob, insisted that in Barack Obama’s White House, ‘cheeseburger’ and ‘hotdog’ were code words for small children - zijn allemaal termen die gebruikt worden voor jongere kinderen. Asked how she knew, she replied that it’s common knowledge.

In De Volkskrant, columnist Loes Reijmer concurred that more and more people believe the craziest things - de gekste dingen geloven, she wrote. Many people now realise that such views are widely held, a serious problem.

Lubach’s target was Lange Frans, “conspiracy rapper” - conspiratie rapper - a label so apt (implying a lyricist’s gift for macho tales of exponential invention and offence) that Lubach might have coined it himself. But Frans really is an actual rapper, one half of Dutch hip hop duo Lange Frans and Baas B who achieved some celebrity from 2004 until they split in 2009.

Born Frans Christiaan Frederiks, Frans worked as a television presenter before turning to You Tube where he attracted 700,000 followers. The rapport between Lange and his guests tallies neatly with the NCTV’s account of the bonds between far-right factions in the DTN report. Rather than a common cause, they reflect shared antipathies.

Lange hangs out with Tisjeboyjay, a fellow rapper and “world improver” - Wereldverbeteraar - according to his avatar on Instagram; a documentary maker, Janet Ossebaard, whose conspiratorial films “expose” Bill Gates; and Wybren van Haga, a former VVD MP who defected to Thierry Baudet’s nationalist and eurosceptic Forum voor Democratie (FvD).

One of the funniest moments is Lubach's bemused reaction to Frans reminiscing with Ossebaard about how the pair met: on a trip to investigate mysterious crop circles in England. Lubach slaps his forehead in mock surprise! Crop circles, of course.

A hop and a skip to the abyss

Now in its 12th series, Zondag met Lubach belongs in a category of old (20th century) terrestrial television formats - a clone of the late-night satirical news programming in the US. Online conspiracists are a slow-moving target: a crazy bunch with fast internet and too much time on their hands, as Lubach said - snel internet en te veel tijd op hun handen.

Lubach deployed his national audience like a sledgehammer to crack a nut. About two million viewers watched clips of Frans eagerly discussing how we are ruled by a satanic, blood-drinking elite - “geregeerd door een satanische, bloeddrinkende elite”.

The longer people spend in such company, argued Lubach, the more receptive they become to ideas amplified by reality-warping power of attention-hungry algorithms. From 9/11, to Malaysian airlines flight MH17, to Bill Gates-is-the-devil: each new conspircacy is click bait leading us down rabbit hole after rabbit hole - konijnhol naar konijnhol.

QAnon is the context for Lubach’s exposé of Dutch social media: an antisemitic end-of-time theory with a violent denouement

After years of clicking on whatever the algorithms deliver to our screens, while everyone simultaneously thought they were deciding for themselves what content to watch, Lubach blames YouTube, Facebook and internet giants. Vying to hold our attention, they funnel users into a ‘trap of tales’ - een fabeltjesfuik - or literally, ‘fable trap’. #fixdefuik, Lubach posted on Twitter.

In a boast which proved fateful, Frans mused breezily about shooting prime minister Mark Rutte: his voice had the tone of a man making a reluctant case for assassination, exasparated by a dearth of other options. He knows how to fire a gun and he could do it, Frans told a guest. But his conscience is addled: he won’t, because the karma would be bad. He prefers to sleep at night.

As befits a morality tale, this big small talk became a metaphorical smoking gun in Lange Frans’s hand.

Within days of Lubach’s broadcast, YouTube closed down Frans’s channel citing repeated and serious violations of its code of conduct. It was a conquest of sorts, and skilful: a rearguard shot from a seasoned showman in the ranks of beleaguered old media which felled an careless upstart among the younger, unruly, largely ungoverned new media.

A line in the ether

In De Volkskrant, Reijmer admitted to feeling a kind of cognitive dissonance. For journalists, exposing the online conspiracists is a step into the virtual world is a departure from their traditional responsibility to keep watch on the real one. Actual reality, the physical world, can be equally twisted but more cruel. She cites gruesome examples to reinforce her point.

If a separating line can still be drawn between virtual and actual, an image from Lubach’s show confirms how much it has frayed. In the small Dutch town of Almelo, population 73,000, graffiti has appeared outside the town hall. The message scrawled on the pavement, in block capitals of increasing size, reads: We worden geregeered door satanische pedofielen. Once a quiet town, said Lubach, now ruled by satanic paedophiles.

People who claim that all politicians are child rapists tend also to believe in QAnon. Lubach didn't mention QAnon by name, but Reijmer credits the conspiracy theory from 2017, attributed to “a supposed intelligence agent” known as Q, as his frame of reference.

According to this account from Wired magazine, Q “maintains that Donald Trump is actually a white knight waging a secret war against a powerful cabal of elite Satanist paedophiles using a secret language involving pizzas and harvesting children’s blood to create an immortality elixir”.

These notions are becoming less marginal. In the UK, research by charity Hope Not Hate found that one in four Britons (17%) believe elements of QAnon conspiracies, including that Covid-19 is part of a deliberate “depopulation plan” for a “new world order”.

The Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a UK think tank, measured 309,652 Q-related tweets in the UK between November 2019 and June 2020. In the US, where the FBI considers QAnon to be a terrorist threat, the comparable figure is more than nine million tweets. (Click here for a video summary of QAnon by ABC News)

Harvesting paranoia, conspiracies spawn and multiply into a hotch-potch of unbordered anxieties. The coronavirus becomes not a health crisis but a deliberate and systematic attack on the economy. A vaccine, when it arrives, would be an excuse to embed microchips in every citizen.

Marcel Gelauff, NoS news editor, blamed President Trump’s hostility to the press. This negative example has spread like an oil slick - als een olievlek verspreid,” Gelauff told Trouw in an interview. (His home address was among those shared on the Telegram messaging app)

This is the globalising subplot, the unacknowledged context of Lubach’s exposé in the Netherlands. Conspiracies travel by familiar routes: fringe ideas shared via social media, amplified by internet algorithms, feeding radicalised far-right beliefs according to similar demographic patterns.

But QAnon is more than its widely-rehearsed rumours, writes Reijmer: a dark end-of-time theory with a violent denouement - een duistere eindtijdtheorie die zinspeelt op een gewelddadige ontknoping. And plainly antisemitic. The notion that children are tortured for their blood is a variant of ‘the blood fairy’ tale - het bloedsprookje.